How to teach children how to save

A (wrong) assumption is that kids don't and should not hear anything about money because "they are kids", "should just think about playing" and different variations of the statements. Well, this couldn't be more far from truth. In fact, kids hear about money basically since the moment they are born. They hear us talking with our partner and friends. They see us using our debit/credit card. They see us buying online and at the grocery store. And anytime tv or radio talks about money, they hear that too.

But that's not all. Money is part of fairy tales, cartoons and animated movies. Think about Scrooge McDuck swimming into a pool of money, Aladdin stealing a treasury (and lamp), Robin Hood that steals (money) from the King. And when kids go to school, they are taught how to calculate the change, and the concept of saving (think The Ant and the Grasshopper fable). Although they do get exposure to money, knowing how to save and manage money is a totally different thing. And in many cases that's what they lack, mostly because they are not thought early enough.

Students and money

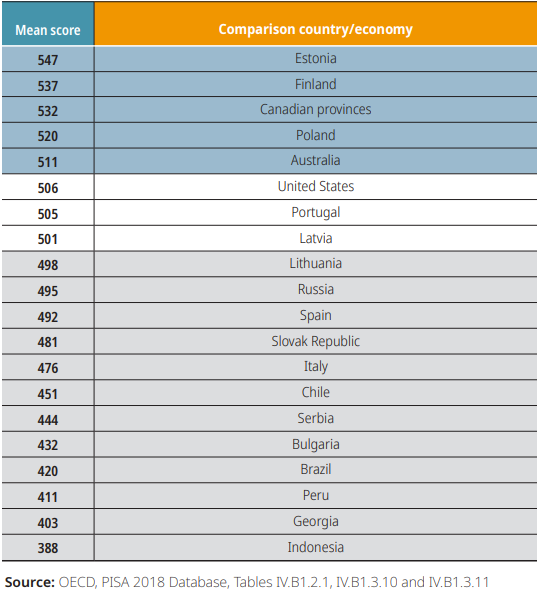

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an intergovernmental organization with 38 member countries, regularly assesses the level of financial literacy. In a study called PISA, they check whether 15 years old know enough about money. Items in the assessment addressed topics such as dealing with bank accounts and debit cards, understanding interest rates on a loan, or choosing between a variety of mobile phone plans.

The ranking below shows how the different countries performed, where the colors indicate if the mean score is above, on par, or below the OECD's aggregated average.

- Estonia had the highest average score, followed by Finland, Canada, Poland and Australia

- Around one in four students in the 20 countries and economies that took part in the latest test, and one in seven in the 13 OECD countries and economies, are unable to make even simple decisions on everyday spending

- Only one in ten students performs at the highest level of financial literacy, on average across OECD countries and economies

- On average, roughly one in two students hold an account at a financial institution and/or hold a payment or debit card; however, only roughly one in three students have the skills to interpret and evaluate a bank statement.

- Parents, guardians and other adult relations are students’ most common source of information about money matters: 94% of students reported obtaining such information from their parents

- Students who obtain information about money matters from their parents scored 38 points higher in the financial literacy assessment than students who do not get it

- Students who reported that they discuss their own spending decisions with their parents once or twice a week performed better than students who reported that they discuss this topic either less or more often

When to start talking about money

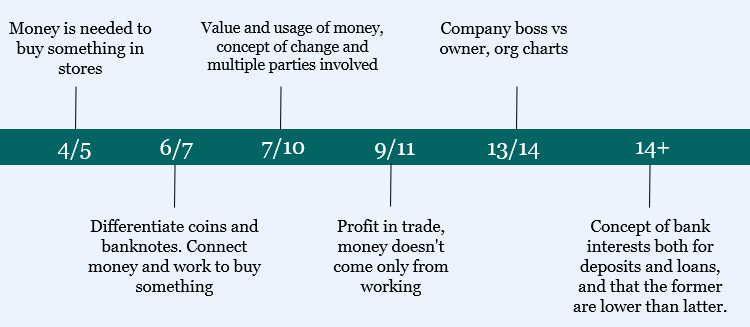

Experts such as Prof. Emanuela Rinaldi, Anna Berti and Ilaria Castelli have identified different stages of development that can be used to introduce different saving concepts:

- Before 4 years: kids don't understand what money is used for

- 4/5 years: kids understand that money is needed to buy something in stores, but they don't understand the concept of price or how money is earned

- 6/7 years: kids can differentiate coins and banknotes but don't understand the concept of change. They start to connect the concept of money and work

- 7/10 years: kids know enough about math to understand the value and usage of money, including the concept of change. They start to understand that there are multiple parties involved e.g. transports of goods

- 9/11 years: kids understand the concept of profit in trade and that sellers must keep the prices right if they want to be able to pay for the expenses and provide for their families. Another key concept learnt is that money doesn't come only from working but also from savings, selling your own assets and inheritance.

- 13/14 years: kids can differentiate the figure of the boss vs owner of the company. They can also understand more complex org charts and unions

- 14+: kids understand the concept of bank interests both for deposits and loans, and that the former are lower than latter.

All the stages above can vary depending on the local context and systems present in different countries.

Should I give pocket money to my kid?

From scientific research perspective there is no clear evidence (valid in every country) that demonstrates that giving pocket money to your kid is a good way to develop financial knowledge or a major inclination towards saving money. However, if done correctly, giving money can be a way to make the kids progressively independent from the family and helps establishing respect and trust towards the kid.

In the 1980s parents preferred to give money upon request to avoid getting kids used to the idea of fixed income, to avoid making them "soft" --> I need to make no effort to make money. Instead it was better to give the money needed ad hoc; this was a chance to discuss the request and talk about money: "Why do you need it?", "Do you need it or want it?".

At some point, without any scientific reason, the fixed income came back in auge, especially in the middle class. People were thinking that a fixed income would help to control purchases without limits of teenagers, develop some planning skills and set a good relationship with money. All without scientific proof.

If giving pocket money to your kids work, keep doing so. If you prefer to give on demand, or pay for small house chores, that works too. The choice of the money allocation in the family should be experimented in a trial-error method, it should work for all the stakeholders involved. In terms of age, 9-10 years is normally appropriate as they understand enough about money.

Finally, how to teach your children to save

Household net saving accounts for 5.5% of household disposable income in the Euro area and for 7.6% in the U.S. (OECD, 2022). Sub-optimal saving is not a local phenomenon and the lack of saving has been related to many factors, from procrastination, lack of financial literacy as well as to the inability to exert self-control and delay immediate gratification.

Different studies, including one by Professors Bucciol and Veronesi titled "Teaching children to save: what is the best strategy for lifetime savings", have investigated what are the key parental strategies on the propensity to save and the amount saved during adulthood. The study showed that parental teaching to save increases the likelihood that an adult will save by 16%, and the saving amount by about 30%. Therefore you can imagine how important it is to teach children how to save early on so that they will increase savings in adult age. The best strategy involves a combination of different methods:

- Give autonomy to the child, in both spending and making money. Doing some simple job (outside home) do help to improve financial competences.

- Teach them how to do a budget: talk about the family budget and help your kid to prepare a personal one. Key concepts such as being able to control income and expenses in a regular way and plan for outflows needed to realize an activity (e.g. a vacation) it's one of the pillars of financial wellbeing. Families sometimes don't discuss money with kids because they are afraid of their questions: "So we are poor?", "Dad how much do you make?", "And mum?". Sometimes the (financial) competences of the parents are not high, but in that case, learning together with the children by listening to a podcast, or simply reading financial news can be a good moment for both to get familiar with terms and concepts. Budget can be thought when they have enough math knowledge, normally 7-8 years old.

- Stimulate the kids towards general financial concepts: money, economy and basic financial concepts are useful topics to stimulate the interest towards financial topics.

- Inspire kids to focus on the future: think about future consequences, plan, make forecasts, etc. An example is start worrying about the pension before they turn 60 by opening a savings account, or even better, an investments account.

All these factors have been proven to help kids become better savers once they grow up. Ultimately in the process where we build our relationship with money there are many factors involved, not just what parents teach: personality, gender, role-models, friends, teachers, social media etc.

The economy pie

Another practical way to teach your kids how to save is to build an "economy pie". The economy pie is a project created by the association FarEconomia in collaboration with different universities in Italy, to teach financial concepts to kids in primary school.

The concept is quite simple. You build a piggy bank divided into 4 parts (or 4 boxes glued together, or 4 jars, etc.) that represent 4 different saving goals:

- Savings for short term: to buy something I wish e.g. buying candies

- Savings for long term: a future project, such as going on vacation with friends

- Savings for someone I love: a birthday present for a friend or relative

- Savings for solidarity: help someone that I don't know

The pie teaches real concepts such as diversification (different slices), time horizons (short vs long projects) and the usage of money to help others. The slices can also be personalized, creating slices for investments or taxes.

If you want to learn how to teach financial wellbeing to your children - that is different from getting "rich", check out my other article.