The psychology of saving: why we spend more than we should - Part I

Do you ever feel like your wallet has a leak? You know, you mean to stash cash away for that dream vacation or, you know, not eating cat food in retirement, but somehow... poof! It vanishes faster than free donuts in the office breakroom. It's like knowing vegetables are good for you, but still reaching for the pizza. You are not alone.

A fundamental challenge in personal finance is the persistent gap between the intention to save and the reality of spending. Many individuals recognize the importance of setting aside funds for future goals, such as retirement, emergencies, or significant purchases, yet struggle to consistently translate this intention into action. Evidence suggests this is a widespread issue; for instance, studies indicate low household saving rates in various economies, with significant portions of the population failing to save regularly or adequately for long-term security. In the U.S., data from Feb 2025 showed that the avg personal savings rate was 5%. But the reality is even worse, as figures from surveys indicate that somewhere between 19% and 27% of US adults report having no emergency savings (Bankrate). And it's not just about how much money you make or whether you aced Econ 101.

What's the plan here? (a sneak peek)

Think of this as peeling back the layers of the financial onion (without the tears, hopefully!). We're going to dive into the nitty-gritty of why we tend to spend too much and save too little, using all the juicy insights from behavioral finance. We'll look at specific brain biases, sneaky psychological triggers that make us open our wallets, how society and even the way we pay (credit card vs. cash) influences us. And most importantly, we'll uncover some science-backed tricks to help us outsmart our own brains and finally get those savings goals on track. Ready to become a financial ninja? Let's do this!

Meet behavioral finance: your brain on money

For ages, traditional economics assumed we're all super-rational robots, always making perfectly calculated choices to maximize our happiness (or "utility,"). But let's be real - when was the last time you made a money decision purely based on logic?

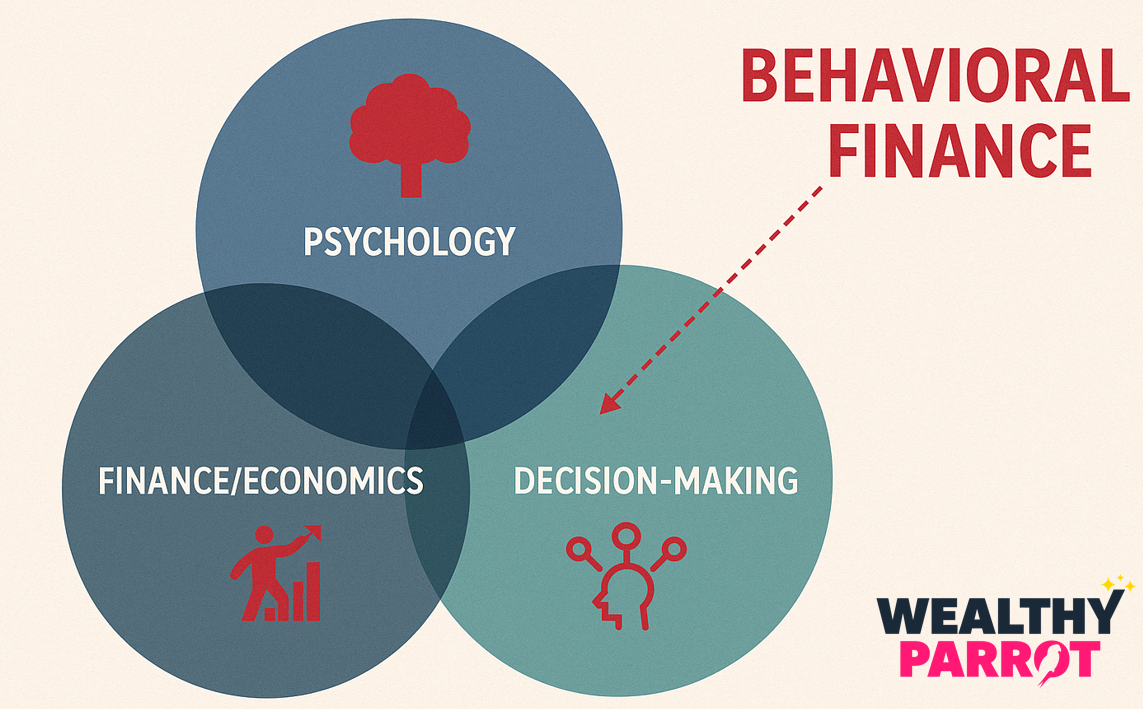

Behavioral finance blends psychology and economics to explore how human behavior, particularly psychological factors, influences financial decision-making. It assumes that financial choices are not always the result of rational calculation, as traditional economic models often assume. Instead, decisions related to spending, saving, and investing are significantly shaped by emotions (like fear and greed), cognitive limitations, systematic biases in thinking, and social influences. The core contribution of behavioral finance lies in its ability to explain why individuals often make financial choices that appear irrational or deviate from their own long-term best interests and stated goals.

Behavioral finance helps explain that nagging paradox: why we know we should save for that rainy day (or, let's be honest, that trip to Bali), but end up splurging on things we don't really need. It's not always about being "bad" with money; it's often about:

- Emotions running the show: fear of missing out (FOMO) on a deal? That sudden urge to "treat yourself" after a bad day? Yep, emotions are big drivers.

- Brain biases playing tricks: things like loss aversion (hating losses more than loving gains), overconfidence (thinking we're investing geniuses after one good stock pick), or herd behavior (buying crypto just because everyone else is) can lead us astray.

- Social pressure: keeping up with the Joneses, or even the Kardashians, is a real thing.

Essentially, behavioral finance shows us that the battle between spending now (hello, instant gratification!) and saving for later (goodbye, immediate fun?) happens right inside our heads. It’s especially relevant for everyday choices like grabbing that fancy coffee versus packing lunch, which happen way more often than big investment decisions.

Your brain's sneaky money habits: what are cognitive biases?

Think of cognitive biases as your brain's attempt to be efficient. It creates mental shortcuts (heuristics) to make decisions faster. Super helpful when you're dodging pigeons, less helpful when you're deciding whether to splurge or save. These shortcuts often lead to systematic errors in thinking, especially about money. They mess with how we see value, risk, and time, often making us grab the shiny thing now instead of planning for the treasure chest later.

1. The "I want it NOW!" syndrome: present bias

Present Bias is our inner toddler screaming for the treat right now, rather than waiting for two treats later. We humans often prefer a smaller, immediate reward (like that impulse buy) over a larger, future one (like a comfy retirement). It's like we think future-us is some other person who can deal with the consequences. Scientists even have a fancy term for the math behind it: hyperbolic discounting. Basically, the value of a future reward drops faster in our minds the sooner we have to wait for it.

Source: Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory

The impact on saving versus spending is direct and profound. Spending money now gives instant gratification - a little dopamine hit! Saving for the future? That feels abstract, maybe even a bit boring. Present bias makes that daily fancy coffee way more appealing than socking away cash for a down payment decades away. Remember the famous Marshmallow Test? Kids struggling not to eat the marshmallow right away for a bigger reward later? That's present bias in action, starting young! It’s why we might pick a pricey monthly subscription over a cheaper annual one - the immediate hit is smaller.

This bias gets a turbo boost when the future looks uncertain or super complicated. Retirement planning? Oh boy. You're trying to guess what life will be like decades from now, factoring in things you can't possibly know for sure.

- Complexity overload: when faced with the mental gymnastics of long-term planning, the simple, certain joy of spending that cash today suddenly looks incredibly attractive. Your brain basically throws up its hands (or wings!) and says, "Too hard! Let's buy the fancy coffee maker instead!"

- Uncertainty scares us: delaying a reward always has that tiny voice whispering, "What if it never actually arrives?" That perceived risk, even if small, makes the guaranteed pleasure of now feel safer, especially if you're the type who doesn't like gambling with your gold.

Adding to the fun, it's genuinely hard to picture yourself decades older. What will you need? What will you want? That fuzzy image of "Future You" doesn't exactly scream "Save for me!" It makes it harder to prioritize distant goals over immediate desires.

2. Ouch, that stings!: loss aversion

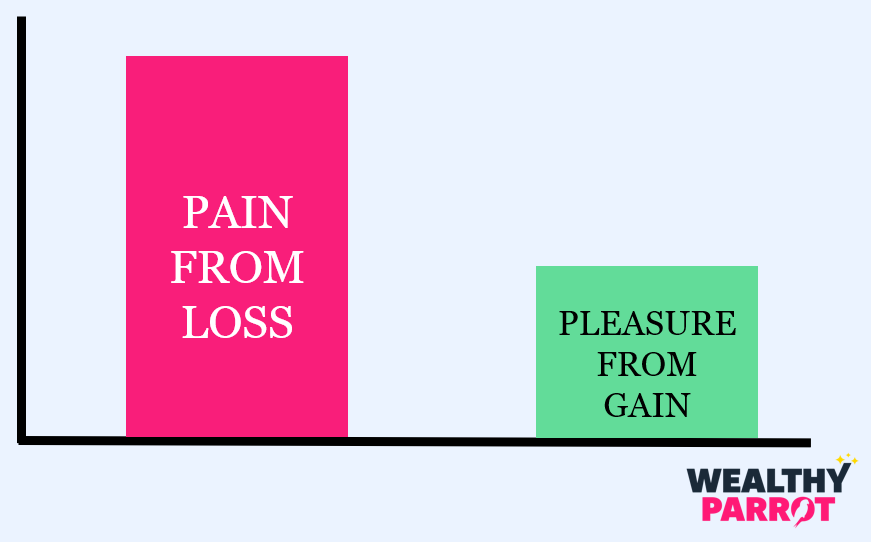

Loss aversion describes a fundamental aspect of human psychology where the negative emotional impact of a loss is significantly greater - often estimated to be about twice as powerful - as the positive emotional impact of an equivalent gain (Kahneman and Tversky). Think about it: losing $50 feels awful, but finding $50 is just... nice. Not "twice as nice," right? Our brains are basically wired to be loss-avoidance machines.

This mental quirk shows up in a few sneaky ways when it comes to saving and spending:

- Playing it too safe: because losing feels so bad, people often stuff their savings under the proverbial mattress (or into super-low-return accounts). They're so terrified of seeing their balance dip even slightly that they miss out on potential growth. It's like refusing to leave your house for fear of tripping – you're safe, sure, but you're missing out on life (and potential investment returns)!

- Saving feels like losing... Right now: here's the paradox: sometimes, the act of saving itself feels like a loss. You're "losing" the fun you could be having with that money today. That immediate sting of "lost" enjoyment can easily overpower the fuzzy, far-off idea of future financial security. Ever gotten a pay cut and found it nearly impossible to spend less? That's loss aversion biting you! Cutting back feels like losing the lifestyle you were used to, and boy, do we hate that. Studies even show that when income drops, savings take a nosedive, but when income increases, savings don't get the same proportional boost. We resist giving up what we have.

- The investor's bad habit (the disposition effect): in the investing world, loss aversion leads to what's called the "disposition effect." This is finance-speak for holding onto investments that are losing money way too long, desperately hoping they'll bounce back (because selling means admitting the loss – ouch!). At the same time, people tend to sell winning investments too quickly to lock in the gain, potentially missing out on further growth. It's like clinging to that awful stock like it's Gollum's Precious, while kicking winners out the door prematurely. Even pro golfers do it – they try harder to avoid going over par (a loss) than they do to get under par (a gain)!

Loss aversion is a master of keeping things exactly as they are – the status quo feels comfy and safe. As we saw, people hate cutting spending when money gets tight because it feels like a painful loss. But guess what? It also makes people sluggish about increasing their savings when they get a raise or bonus! Why? Because your current spending habits are your baseline. Saving more means actively losing some of that spending money you've gotten used to, even if you technically have more overall. That immediate, tangible "loss" of fun money often feels more real than the distant, abstract "gain" of a bigger retirement fund. So, next time you're hesitant to save a bit more or cut a losing investment loose, remember this quirky brain wiring

3. Stuck on the first number: anchoring bias

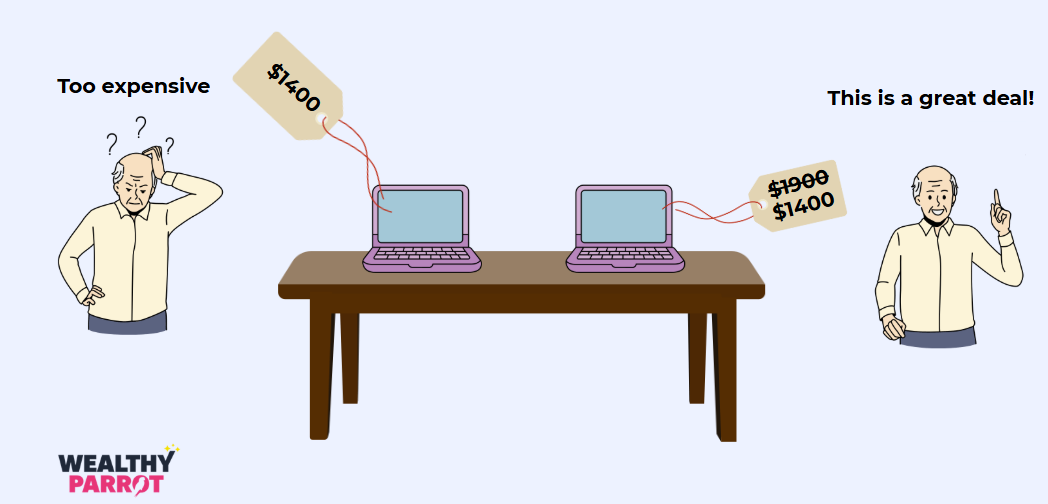

Anchoring bias is the cognitive tendency to rely heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the "anchor") when making decisions. Ever walked into a store, saw a ridiculously priced jacket for $1,000, scoffed, and then thought, "Wow, this $200 one next to it is a steal!"? If so, you've just been hit by a sneaky little brain quirk called Anchoring Bias.

Think of it like this: your brain is a bit like a ship captain who really likes the first port they dock at. That first piece of information – the anchor – gets dropped, and suddenly, everything else is judged based on that initial spot, even if the anchor itself was dropped in totally the wrong place!

This bias means we latch onto the first number or piece of info we get when making decisions. Even if that first number is totally random, like a squirrel guessing lottery numbers, we tend to adjust our thinking from that starting point, but usually not enough.

Marketers frequently leverage anchoring by displaying a high initial price (e.g., a manufacturer's suggested retail price or an inflated original price) before revealing a lower "sale" or "discounted" price.

- The "Original price" illusion: ever see that "Was $500, Now $250!" tag? That $500 is the anchor. It makes the $250 look like the deal of the century, even if the item was never really intended to sell for $500. Sneaky, right? You feel like you're winning, grabbing that bargain (hello, transactional utility!).

- Big ticket anchors: that car salesman showing you the fully-loaded $60,000 beast first? He's anchoring you high, so the $45,000 model suddenly feels way more reasonable. Same goes for seeing a $1,200 t-shirt (who buys that?!) making a $100 one seem downright cheap, or a fancy $600 gift basket making the $300 option look appealing.

- Negotiation nightmares: your first salary offer? The asking price for that house? Boom! Anchors dropped. Everything that follows is a tug-of-war around those initial numbers.

Anchoring doesn't just mess with shopping; it messes with our own budgets and expectations.

- The vacation trap: remember that charming beach house you rented for $180 a night five years ago? Now similar places are $300. Your brain, anchored to $180, screams "Rip off!" even if $300 is the fair market rate today.

- Investing oopsies: bought a stock at $50, and now it's tanked to $20? The anchoring bias whispers sweet nothings like, "Just hold on until it gets back to $50!" even if the company's fundamentals have gone down the drain. You're anchored to the purchase price, not the current reality.

Anchoring plays a huge role in lifestyle inflation - the tendency for spending to increase as income rises. Your first "real job" salary? That becomes an anchor for your spending habits. You get a raise – yay! Your income goes up, and naturally, your spending drifts up too. Now, that new, higher spending level becomes your new anchor. Suddenly, saving that bonus feels like deprivation because you're comparing it to your new "normal" spending anchor. Cutting back feels like a loss. It's like your brain gets stuck on the current level, making it psychologically tough to funnel those income gains into savings instead of just… spending more. It’s a classic case of the hedonic treadmill, where you keep running just to stay in the same place, happiness-wise, but your wallet gets lighter!

4. Different piles of cash: mental accounting

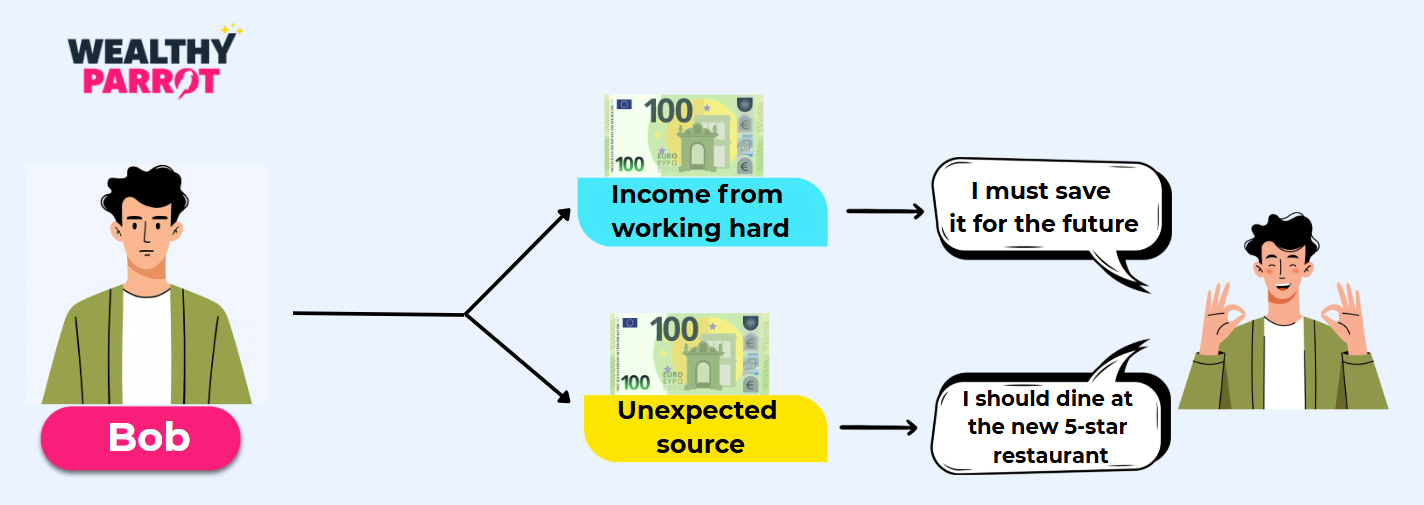

Okay, picture this: you get a crisp $100 bill for your birthday. Awesome! What do you do? Maybe splurge on something fun you wouldn't normally buy. Now, picture earning $100 after a long, hard week at work. Same amount, right? But does it feel the same? Maybe that earned $100 feels more "serious," destined for bills or savings. If this sounds familiar, congratulations, you've stumbled into the weird world of Mental Accounting!

Think of your brain like it has a bunch of different labeled jars for money: the "Rent jar," the "Groceries jar," the "Fun weekend Jar," the "Someday vacation jar." Mental accounting is our quirky habit of treating cash differently depending on which jar we mentally toss it into, even though, let's be real, money is money! It's all interchangeable, or in finance jargon, fungible.

Sometimes these invisible jars make us do financially not ideal things.

- The debt vs. savings paradox: ever kept money chilling in a savings account earning practically nada (like 1% interest) while simultaneously paying off credit card debt that's charging you a whopping 20%? Logically, you should use the savings to zap that expensive debt. But nope! Mental accounting puts up a wall: "That's my Savings Jar money, I can't touch it for Debt Jar problems!" It's like meticulously watering your houseplants while ignoring the fact your kitchen is on fire.

- The "Found money" free-for-all: tax refund? Surprise bonus? Inherited $50 from Aunt Mildred? Often, this gets mentally labeled "Fun Money" or "House Money" (like casino winnings). Instead of treating it like any other dollar – saving it, investing it, paying down debt – we feel freer to spend it on stuff we might not otherwise buy. The source changes how we value it.

- Digital funny money: those gems, coins, or tokens in apps and games? They exploit this! Spending 1000 "Sparkle Points" feels less painful than spending $10 of actual currency, even if they represent the same value. It creates a mental distance, potentially tricking us into spending more.

Basically, these mental partitions prevent us from seeing the big picture. We optimize within our little jars, forgetting that all the money could work together much more effectively.

Mental accounting isn't all bad it can be strategically harnessed as a tool for improving financial behavior. If done right, the same tendency to separate funds can be turned into a superpower for saving!

- Intentional jars (the good kind): instead of letting your brain do it unconsciously, you take control. Deliberately set up actual separate accounts or budget categories: "Emergency fund," "Dream vacation," "Retirement nest egg," "New gadget goal." These are normally referred to sinking funds.

- Building walls against yourself: by earmarking funds for specific goals, you make them feel more real and protected. That "Emergency fund" jar feels different from your general "Spending money" jar. You mentally wall it off, making you less likely to raid it for everyday coffees or impulse buys.

This way, you're using the brain's own weird wiring as a self-management trick. You're turning a potential bug into a feature, nudging yourself towards better financial habits by making your savings goals concrete and defending them with mental barriers.

5. The new-thing shine wears off: hedonic adaptation

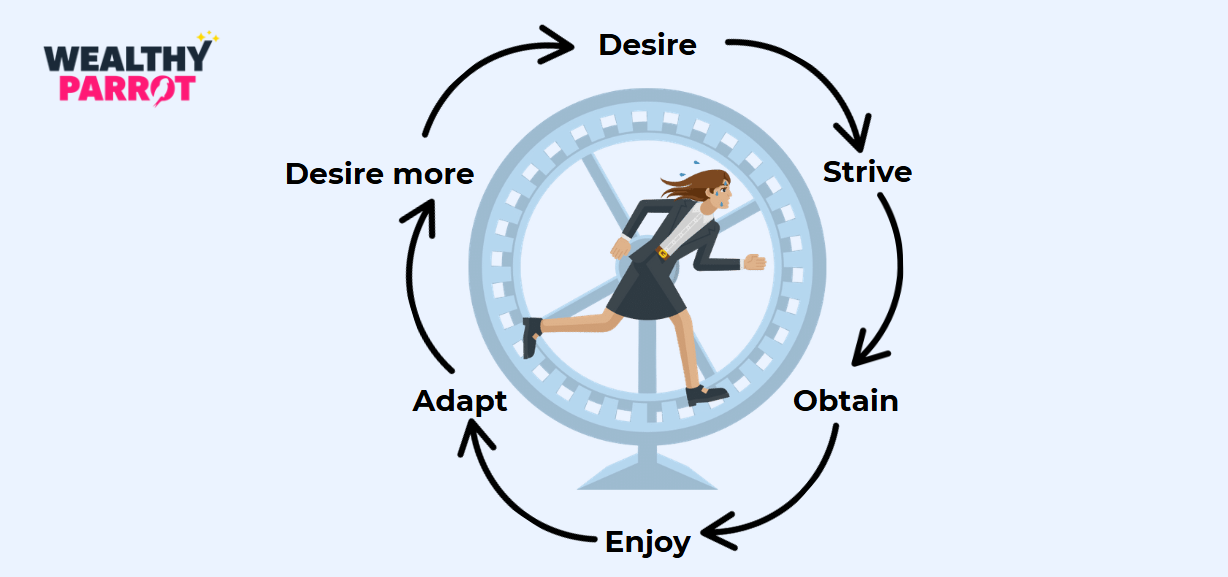

Do you remember the absolute thrill of getting that brand new phone, that shiny car, or that amazing pay raise? You felt like you were walking on sunshine, right? Fast forward a few months... and meh. It's still nice, sure, but the initial fireworks have fizzled. Welcome, my friend, to the Hedonic Treadmill, also known as Hedonic Adaptation!

Think of it like this: your happiness level is kinda like being on a treadmill. You get a boost (like a promotion or a fancy new gadget), and you feel like you're sprinting ahead! But pretty soon, your internal happiness-o-meter adjusts, and you're back to your usual jogging pace, even though your circumstances are objectively "better." You adapt, get used to the new awesome thing, and baseline happiness just... resets.

This treadmill effect has some serious sneaky consequences for our wallets:

- The never-ending quest for the next buzz: that rush from buying something new? It fades. Like, really fades. So, what does our adaptation-prone brain tell us? "Go get another buzz! Buy something else!" This fuels a constant cycle of wanting and buying just to get that temporary hit of pleasure again. Exhausting, right?

- Yesterday's luxury is today's normal: remember when having streaming and cable felt like peak luxury? Now it's just... Tuesday. As we get used to a higher income or a nicer standard of living, our expectations creep up. What used to feel special becomes the new baseline "normal." This means we feel like we need to spend more just to stay at the same level of satisfaction. Hello, lifestyle inflation! It makes saving feel like deprivation because we've adapted to the higher spending level.

- Saving? why bother (eventually)? That initial excitement from a raise might make you think, "Yes! I'm going to save so much!" But as you adapt to that higher income, the motivation can dwindle. The extra cash just becomes part of the expected landscape, not a special bonus to be carefully managed. Even lottery winners, studies show, often end up back at their pre-win happiness levels after the initial euphoria wears off!

- Marketers know: they sometimes tap into this by creating fake urgency ("Limited time offer!") to get you to buy before your desire naturally adapts and fades.

Our happiness treadmill isn't running in a vacuum. It's running right alongside everyone else's treadmill, and nowadays this means the ones we see on social media. This is where Social Comparison turbocharges the whole process. We don't just adapt to our own stuff; our baseline happiness level gets heavily influenced by what we see around us.

- You get a nice new car. Yay! Initial happiness boost.

- You adapt. The car is now just... your car. Baseline reset.

- BUT THEN, you see your neighbor/friend/random influencer showing off their even newer, fancier car.

- Suddenly, your perfectly good car feels kinda... meh. Your reference point for "normal" or "good enough" shifts because of what they have.

- Dissatisfaction kicks in, and the urge to upgrade (and spend!) hits again.

This deadly combo of adapting to our own gains and constantly comparing ourselves to others creates a relentless cycle. We adapt, we compare, we desire more, we spend more, we adapt again... and the treadmill just keeps spinning faster and faster, making it incredibly hard to feel content and even harder to get ahead financially.

6. Other influential biases

Beyond the biases discussed in detail, unfortunately there are several others that could impact your tendency to overspend and under-save:

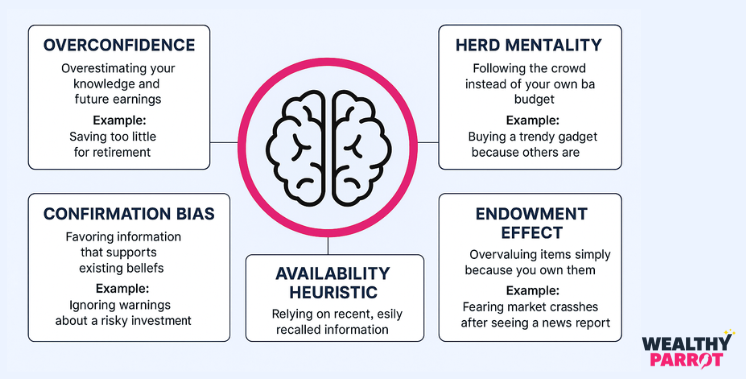

- Overconfidence: ever felt absolutely sure you know more than you do about money, or that you'll definitely earn way more next year, or that you've totally got your spending under control? That's overconfidence! This misplaced swagger can lead to skimping on savings ("Ah, I'll save tons later!") or taking on way too much debt or risky investments because you overestimate your genius.

- Herd mentality: You see everyone buying that trendy gadget, flocking to that new restaurant, or maybe even adopting certain spending habits within your social circle. Suddenly, you feel an urge to jump in too, right? That's Herd Mentality, often powered by a serious case of FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out). Instead of asking, "Does this fit my budget and my goals?", your brain follows the crowd, assuming they know best (or fearing being left out). This can lead to impulsive buys that don't actually serve you.

- Confirmation bias: confirmation bias is our tendency to hunt for and favor information that confirms what we already believe, while conveniently ignoring anything that challenges our views. Want that expensive new thingamajig? Your brain will expertly find all the articles and opinions saying "Buy it!" while turning a blind eye to the flashing red lights of your budget. It reinforces bad habits and can stop you from considering smart saving or investing strategies if they don't fit your current worldview.

- Availability heuristic: our brains are lazy sometimes. When making decisions, we often rely on whatever information pops into our heads most easily. This is usually stuff that's recent, super vivid, or emotionally charged. Saw a scary news report about a market crash? Suddenly, investing feels terrifying, even if crashes are rare (Availability Heuristic!). Constantly bombarded with ads for luxury vacations? That might make spending on a trip feel more "normal" or urgent than it really is. We overweight the easily remembered stuff, even if it's not the most rational input.

- Endowment effect: ever tried selling something you own and felt like it was worth way more than what people offered? Or found it weirdly hard to declutter, even if you don't use half that stuff? That's the Endowment Effect! We tend to value things more simply because... well, they're ours. It's like putting emotional googly eyes on our possessions. This bias, related to our fear of losing things (Loss Aversion), can make it tough to make smart financial moves like selling assets or downsizing, even when it makes perfect sense on paper. We get stuck with our stuff just because it's our stuff.

Interesting so far? Then head to part II where we'll cover more triggers and solutions you can implement today to don't fall into these psychological traps!