The Wall Street zoo: why finance speaks in animal metaphors

Ever wonder why grown adults worth millions talk about bulls, bears, and dead cats when discussing your retirement fund? Buckle up - we're about to explore the fascinating psychology behind the financial animal metaphors that run Wall Street.

Picture this: You walk into a financial advisor's office, and within five minutes they've mentioned bulls charging, bears hibernating, and hawks circling. You start wondering if you accidentally wandered into a nature documentary instead of a wealth management meeting.

This isn't just colorful Wall Street jargon. These investment metaphors are brilliant psychological tools that have shaped how we understand money for over 300 years. Once you crack the code, you'll never look at market movements the same way again.

Ready to become fluent in financial fauna? Let's dive in!

The original gangsters: bulls vs. bears

The world's first major financial animal metaphor emerged in smoky London coffee houses around 1700, and it involved selling bear skins you didn't actually own. Back then, "bearskin jobbers" would sell bear pelts before actually catching the bears (basically the 18th-century version of short selling). When the South Sea Bubble crashed in 1720, these speculators made fortunes betting against everyone else's optimism.

Bulls came next as the natural opposite - because nothing says "market confidence" like a 2,000-pound animal charging forward with its horns pointed skyward.

Your brain instantly gets it. Bulls thrust up (rising prices), bears swipe down (falling prices). As the legendary investor Benjamin Graham put it, in the short term, the market isn't a "weighing machine" that rationally assesses value; it's a "voting machine" driven by emotion, swinging from the wild optimism of a bull market to the deep pessimism of a bear market.

Fun fact: The stats back up the story. In the post-WWII era, the median bull market charged ahead 76% and lasted about 38 months. The median bear market, in contrast, swiped prices down by 28% and hibernated for roughly 15 months.

The political invasion: when animals left Wall Street

Some of the most powerful animal metaphors didn't stay confined to the trading floor. They became so effective at describing human behavior that they broke out and conquered the world of politics, shaping laws and defining presidencies.

Lame ducks: from bankrupt traders to politicians

Originally, "lame ducks" described broke London traders who would "waddle out of the alley" after losing everything. By the 1860s, American politicians had adopted the term for officials serving out final terms, and the metaphor worked so well it literally changed the Constitution - the 20th Amendment became known as the "Lame Duck Amendment."

Fun fact: The term "lame duck" was used in American politics as early as the 1830s, but it was the incredibly long four-month gap between Abraham Lincoln's election in November 1860 and his inauguration in March 1861 - during which the South seceded - that truly highlighted the dangers of a powerless, lame-duck presidency.

The Fed's flying squad: hawks vs. doves

Picture the Federal Reserve as a giant bird sanctuary where officials, who set monetary policy, get sorted into two species:

- Hawks = Inflation fighters who favor higher interest rates.

- Doves = Employment-focused officials who prefer lower rates.

This isn't just chatter; it leads to one of the oldest adages on Wall Street: "Don't Fight the Fed." When the Fed is in a dovish mood, it's generally a green light for the bull. When the hawks are circling, the bear often wakes up. In the era of Quantitative Easing, the Fed's dovishness became so powerful that some traders nicknamed it "the Grinch Who Stole Distressed," because its actions prevented deep market pain.

Fun fact: Algorithms now use natural language processing (NLP) to scan Federal Reserve statements for "hawkish" or "dovish" words. A single word change in the official announcement can cause billions of dollars to move in the bond market within milliseconds.

The strategy pens: when animals define investors

What if an animal could be your entire investment strategy? Moving beyond the open plains of market-wide sentiment, we now enter the strategy pens. In these enclosures, you'll find animals that don't just represent a mood - they represent a specific, repeatable tactic for building a portfolio.

Dogs of the Dow: the laziest (and most brilliant?) contrarian strategy

Ever wish you could build a blue-chip portfolio with a strategy so simple it feels like cheating? Welcome to the weirdly effective world of the Dogs of the Dow.

At the start of the year, you find the 10 stocks in the elite Dow Jones Industrial Average with the highest dividend yield. You buy them. You hold them for a year. Then you repeat. A high yield often means a beaten-down stock price, so you're betting on the comeback of these unpopular "dogs." It’s a disciplined, almost robotic way to fight herd mentality and embrace value investing.

Fun fact: The strategy was popularized by Michael B. O'Higgins in his 1991 book, Beating the Dow. For decades, it has shown a remarkable tendency to outperform the Dow Jones average.

The conceptual creatures: when animals are big ideas

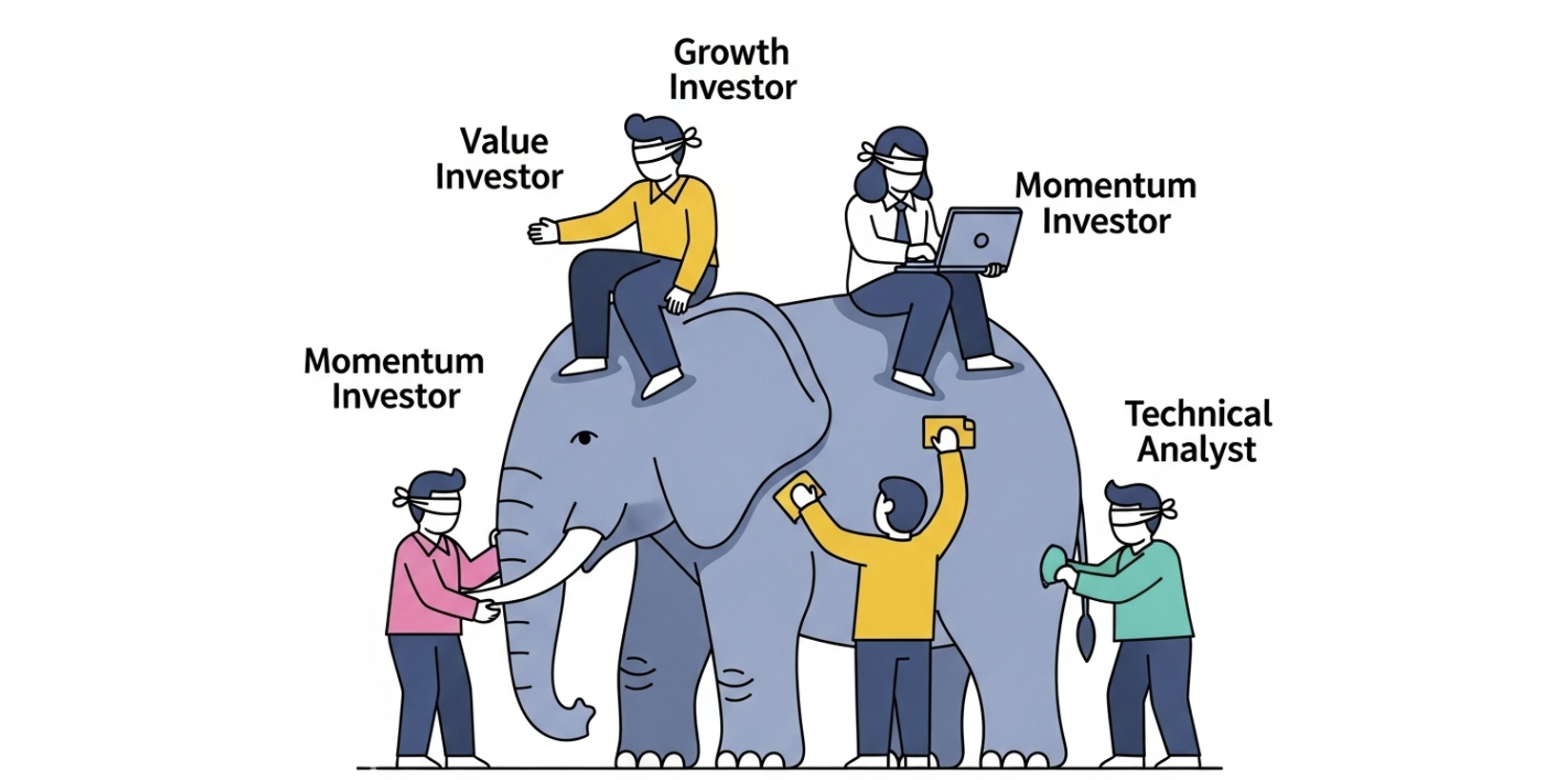

Beyond the market players and specific strategies, the most philosophical wing of the zoo is home to conceptual creatures. These animals aren't just symbols; they are living parables, embodying the complex ideas and paradoxes that every investor must eventually face, from the limits of our own perspective to the problems that come with success.

The elephant in the room: the perils of size and perspective

Remember the old parable about the blind men and the elephant? One touches the leg and swears it's a tree. Another feels the trunk and is convinced it's a snake. This is the Elephant problem in finance - analysts often focus on one part of the picture and miss the whole beast.

But the elephant is also a warning about success: asset elephantiasis. When a fund gets so big, it becomes a clumsy giant, unable to buy or sell stocks without moving the entire market. It's the ultimate paradox of success.

The modern bestiary: digital age animals

As finance grew more complex and global in the 20th and 21st centuries, the zoo needed new, more abstract creatures to explain sudden shocks, mythical valuations, and the new breeds of financial hunters.

Black swan: when "impossible" becomes reality

Nassim Taleb transformed a 2,000-year-old concept into essential investment vocabulary. A Black Swan is a rare, high-impact event that seems "obvious" only in hindsight. Think COVID-19 or the 2008 crash. The problem? We're terrible at predicting them because there's nothing in the past that can convincingly point to their possibility.

Fun fact: Nassim Taleb, who popularized the term, vehemently argues that the 2008 financial crisis was not a Black Swan, as he believes it was entirely predictable. He reserves the term for truly unforeseeable events, not failures of imagination.

Gray rhino: the threat we ignore in plain sight

But what about the dangers we do see coming? Meet the Black Swan's less famous but arguably more important cousin: the Gray Rhino.

Coined by author Michele Wucker, a Gray Rhino is a large, obvious, and highly probable threat that we ignore until it's too late. Picture a two-ton rhino in the distance, pawing the ground. You see it. You know it's dangerous. And yet, you do nothing until it's charging right at you. That's a Gray Rhino. Think of a blatant housing bubble or years of ignored warnings about climate change.

The lesson here is a powerful one: many of the biggest disasters aren't a failure of prediction, but a failure of action.

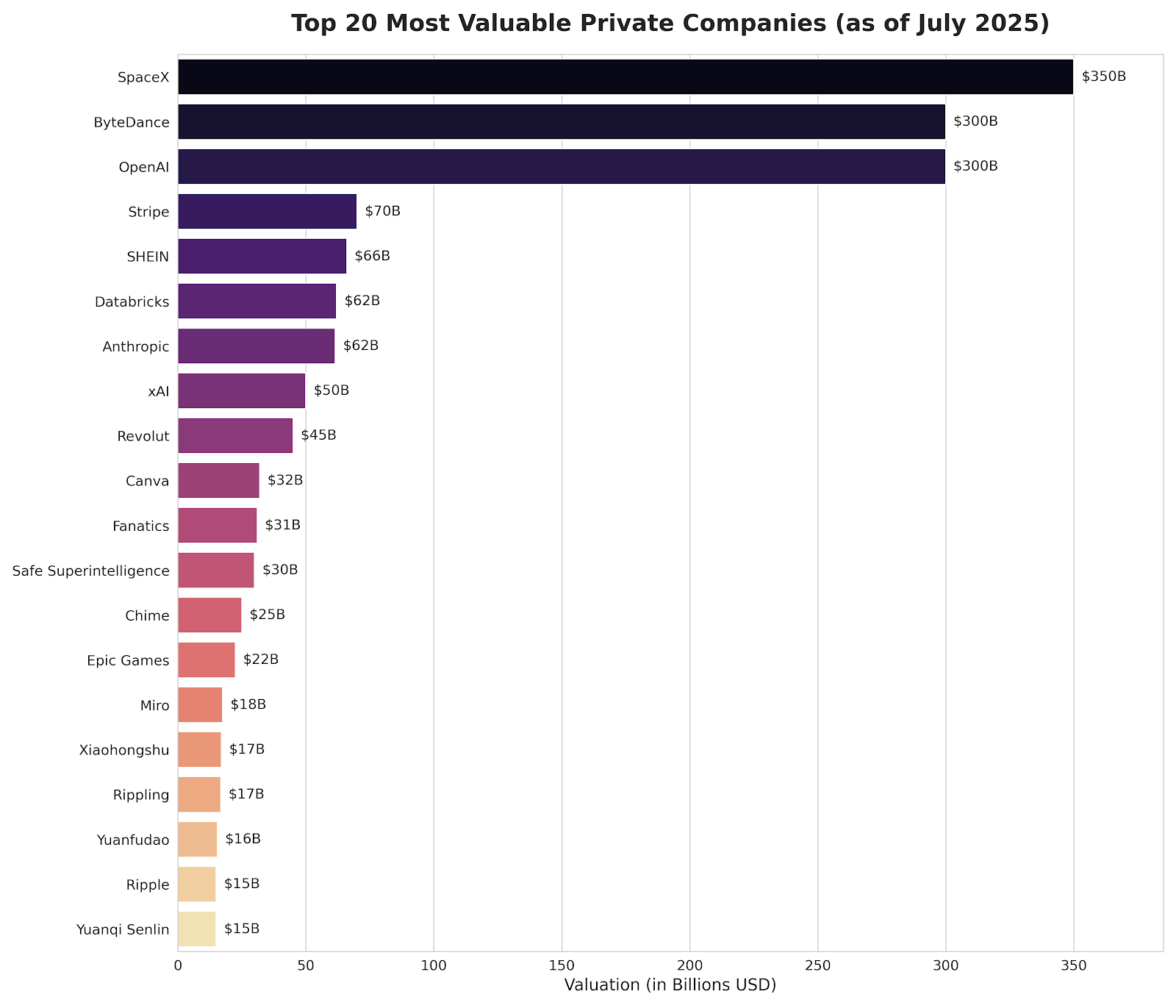

Unicorns: when mythical creatures become billion-dollar businesses

In 2013, venture capitalist Aileen Lee coined "unicorns" for private startups worth over $1 billion. She found just 39. By 2024, there were over 1,200. This has spawned its own mythical lineage: Decacorns ($10B) and Hectocorns ($100B).

A deep dive into the Global Unicorn Club reveals it's less of a club and more of a steep, treacherous mountain. While over a thousand companies have reached the $1 billion Unicorn base camp, only an elite few ascend to become Decacorns ($10B+), with just three legendary Hectocorns standing at the absolute peak. This exclusive zoo is heavily concentrated in just two countries - the United States and China - with most of these creatures thriving in the digital forests of Enterprise Tech and Fintech.

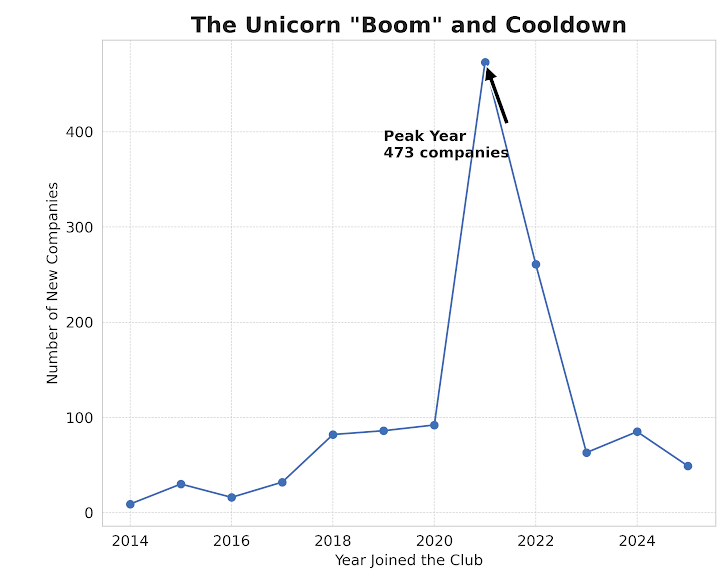

The story of this population is also one of dramatic boom and bust. The club saw a wild, unprecedented surge in 2021, when nearly 500 new unicorns were born in a single year- a speculative frenzy that has since cooled dramatically.

This "meteor shower" moment serves as a powerful reminder that while the hunt for billion-dollar startups is a global obsession, their creation is subject to fierce market cycles, and the path to becoming a true market giant is extraordinarily rare.

Fun fact: Despite their mythical status, many unicorns struggle after going public. A 2021 study found that around 60% of tech unicorns that had an IPO between 2010 and 2020 were trading below their initial offering price a year later.

The predators' corner: sharks and vultures

Not all animals in the zoo are passive trends; some are active hunters looking for their next meal.

- Sharks: In the world of corporate finance, "sharks" are aggressive investors or companies that try to take over other companies in hostile bids. The target company, in turn, will deploy "shark repellent" - defensive strategies to make themselves harder to acquire. The term has become more mainstream thanks to the TV show Shark Tank, where entrepreneurs pitch their ideas to a panel of sharp-toothed investors.

- Vultures: Even more predatory are the "vulture funds." These are hedge funds that specialize in buying the debt of "dying" entities - a company on the verge of bankruptcy or a country close to default - for pennies on the dollar. They then wait for the situation to stabilize slightly before using aggressive legal tactics to sue for the full value of the debt, often making enormous profits from the misfortune of others.

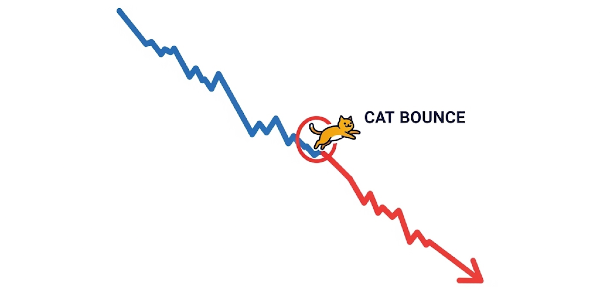

Dead cat bounce: the morbid reality check

Yes, finance people really looked at market crashes and though, "This reminds me of falling cats." The concept: Even a dead thing can bounce if dropped from high enough. In market terms, a sharp, temporary rally during a major decline isn't a recovery - it's just a dead cat bounce.

Fun fact: The term is believed to have been coined in December 1985 by a Financial Times journalist describing a temporary rally in the Singaporean market.

The digital zoo: when the internet creates animals

The rise of cryptocurrency and online forums like Reddit didn't just democratize trading; it created entirely new habitats where digital animals could be born and evolve at lightning speed.

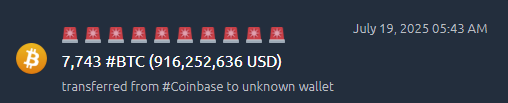

Whales: the unseen giants of crypto

Imagine the crypto market is a vast ocean. Most of us are small fish, swimming along. But hidden in the depths are the Whales - anonymous individuals or entities holding such enormous amounts of a cryptocurrency that their every move can create tidal waves.

In the regular stock market, large investors have to disclose their positions. In the often-unregulated world of crypto, a Whale can be completely anonymous. This has led to a fascinating spectator sport called "whale watching," where traders use services that monitor the blockchain to track massive transactions in real-time. It’s the crypto equivalent of having a sonar system to detect submarines - you don’t know who the captain is, but you know a giant is on the move, and you'd better prepare for the wake.

Apes: the Reddit rebellion

Then came 2021 and the GameStop saga, which gave birth to a new kind of stock market animal, one forged in the fires of Reddit forums like r/WallStreetBets: the Ape.

To be an "Ape" has less to do with traditional analysis and more to do with a cultural identity. It signifies a retail investor who, as part of a massive online community, buys into heavily-shorted stocks as a form of rebellion against Wall Street institutions. Their motto, "Apes together strong," is a declaration that millions of small investors, when united, can challenge the power of giant hedge funds.

Fun fact: The "Ape" movement was heavily influenced by Keith Gill ("Roaring Kitty"), who invested approximately $53,000 in GameStop. At the peak of the frenzy, the value of his position reportedly topped $48 million.

This movement even created its own language. If you want to speak Ape, you need to know terms like:

- Diamond Hands (💎🙌): Holding an investment with extreme conviction, refusing to sell even during massive price drops. The opposite of "paper hands."

- Tendies: Slang for profits or financial gains, derived from chicken tenders.

- To the Moon (🚀): The ultimate rallying cry - the hope that their chosen stock will skyrocket to unbelievable heights.

The Ape phenomenon was a landmark event, blurring the lines between investing, entertainment, and a full-blown cultural movement.

The dark side of financial animal metaphors

But the financial zoo isn't all fun and games. These powerful mental shortcuts can also be used as weapons, reinforcing harmful stereotypes and even obscuring scientific reality.

When a name does harm: the PIIGS

Ever notice how a simple nickname can turn into a weapon? That's exactly what happened during the European debt crisis. Financial media needed a catchy shorthand for the troubled economies of Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain. They came up with "PIIGS."

The name was clever, but it was also a character assassination. It cleverly shifted the blame. Suddenly, the problem wasn't complex Eurozone economics; it was that these countries were supposedly lazy or greedy 'pigs'.

It became a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you call a country a pig, global investors start treating it like one, demanding higher interest rates and making the economic crisis even worse. The metaphor itself became part of the financial damage.

Fun fact: The term became so toxic and was criticized so heavily that major outlets like the Financial Times eventually banned its use, but not before the damage was done.

When the science is wrong: the "alpha wolf"

Let's talk about the biggest, most persistent myth roaming the halls of Wall Street: the "alpha wolf." We've all seen the movies. The lone-wolf trader, screaming into two phones at once, dominating the trading floor through sheer force of will and aggression. It's a powerful image that has built a culture of cutthroat individualism.

There is only one little detail... the science it's based on is completely, utterly wrong.

The very researcher who popularized the "alpha wolf" concept in the 1970s, Dr. L. David Mech, has spent the last few decades trying to publicly correct his own early mistake. He discovered that wolf packs in the wild don't have a brutal alpha who fights his way to the top. They're just... families. The "alphas" are simply the parents, leading and teaching the pack through experience. Real wolves succeed through teamwork.

So, the ultimate symbol of Wall Street aggression is based on a scientific misunderstanding. The funny thing is that the most successful long-term investors, like Warren Buffett, often build their success on the wolf pack's true values: cooperation, trust, and a long-term family mindset. Maybe we should be talking about 'wolf pack investing' instead.

The global zoo: not all animals speak the same language

Financial animal metaphors aren't a universal language. Assuming a bull in Beijing acts like a bull in Boston is a recipe for disaster. Let's take a quick world tour of the global zoo.

Nowhere is the zoo more different than in China. First, colors are inverted: Red means gains (luck) and Green means losses, the exact opposite of the West. Their Dragon (龙, lóng) isn't a monster to be slain, but a divine symbol of power and prosperity, with the top companies being called "dragon head stocks." Perhaps the most vivid local metaphor is the "leek" (韭菜, jiǔcài) - a term for retail investors who are repeatedly "harvested" (lose their money) by bigger players, only to grow back for the next cycle.

In Japan, the language itself creates a unique creature. The word for stock, kabu (株), is a homophone for turnip, kabu (蕪). This famous pun is the entire basis for the "stalk market" in the Nintendo game Animal Crossing!

The future zoo: what's coming next?

The menagerie is far from complete. As technology, society, and our understanding of markets evolve, new creatures are constantly being identified in the wild.

The factor zoo, when academics get overexcited

Imagine you're a financial biologist, trying to pinpoint the specific genetic traits that help a stock "survive" and "thrive" in the wild market jungle. These underlying traits are what academics call "factors."

Let's break this down. In the old days, the zoo was small. The original "zookeepers," Nobel laureates Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, identified a few powerful species that seemed to explain most of the market's behavior. The most famous were:

- Value: The tendency for "cheap" stocks to outperform "expensive" ones.

- Size: The tendency for small-company stocks to outperform large-company stocks.

- Market Risk: The basic idea that taking on more risk should come with a higher expected return.

For decades, this was the core of the financial ecosystem. But then, computers got exponentially more powerful and academics got ambitious. They went on a full-blown "factor safari," testing thousands of potential traits to see what predicted success. Does a stock perform better if its ticker is three letters? If its CEO has an MBA?

This led to a population explosion. Hundreds upon hundreds of new "factors" were "discovered," and economist John Cochrane jokingly called the resulting mess the "Factor Zoo." His warning was that most of these new "species" aren't real; they're just statistical ghosts found by data mining - the practice of torturing past data until it confesses to anything. It’s a powerful reminder to be deeply skeptical of any "newly discovered" secret formula for beating the market.

AI and algorithm animals

The financial jungle is changing. The familiar roars of bulls and groans of bears are being drowned out by a new, digital hum. The zoo is going robotic.

The old animal metaphors were based on human psychology, but an algorithm doesn't "feel" greedy or fearful; it just executes code at inhuman speeds. This creates new mechanical species with behaviors the old zoo can't explain.

We're now seeing the rise of "algo swarms," where thousands of trading bots react to the same signal at the same microsecond, creating violent price swings out of nowhere. These swarms can trigger bizarre events like a "Flash Crash," where the market plummets and recovers in minutes. There are even predatory bots that engage in "spoofing"—placing huge, fake orders to trick other algorithms, only to pull them at the last nanosecond to profit from the confusion.

Fun fact: High-Frequency Trading (HFT) firms measure their success in microseconds (millionths of a second). They pay millions to place their servers in the same data centers as the stock exchanges just to shave off tiny fractions of a second in travel time for their trading signals.

Conclusion: your field guide to the financial jungle

Ultimately, the Wall Street Zoo is just a collection of stories we tell ourselves about money. Your job is to be the one who knows how to read them. From now on:

- Listen like an insider: When you hear 'bull market,' you now understand it as 'widespread optimism.' When you hear 'whale,' you understand it as 'concentrated power.'

- Recognize the bias: Know that a 'sheep' isn't just a follower; it's a warning against your own herd instincts.

- Use it, don't abuse it: Leverage these shortcuts for quick understanding, but never let a cute name replace hard numbers.

The animals are here to stay. Learning their language doesn't just make you sound smarter - it makes you a smarter investor. Welcome to the zoo. 🦜