Accounting 101: income (or profit & loss) statement

The income statement is also called a profit and loss statement, P&L, statement of earnings, or statement of operations. The first important observation is that, as I covered in the financial statements introduction post, the income statement does not show the cash-in and cash-out of the company but rather revenues, expenses, and profit (or loss) for a period of time, such as a month, quarter, or year. This also mean that values are referred to a specific fiscal period (while the balance sheet is not).

In practical terms, as soon as a company has sold a product or service, it registers the sale on the revenue line, even though it might be paid months later (the norm is at least 30 days). During that period the company will have to manage the operating expenses and salaries using money it has (hopefully) accumulated in the previous periods.

When analyzing an income statement, often experts refer to its top and bottom line. With top we're referring to the revenues (from sales), while with bottom we're looking at the net profit, also known as net income or net earnings. The reason while they're called like that is, surprise surprise, that if you look at an the income statement they are the first and last items in the list.

Income statement: revenues

Revenue or sales refers to the value of what a company sold to its customers during a given period. Revenue are normally grouped under one item only, that indicates the value of the goods and/or services sold. A company might distinguish between gross and net revenue. The latter excludes discounts and allowances given to the customers.

Revenue are recorded (or recognized in accounting vocabulary) when they are realized and earned – not when cash is received. This changes based on the product or services is sold by the company, for example attorneys normally charge per hours and present the invoice after work is completed. Companies can also bill clients based on the amount of work completed (e.g. Construction). These are just two examples but there are other options. Overall companies withing the same industries tend to be consistent in how they bill.

Income statement: costs

Costs can be broken down at different level, but some common categories are:

- Costs of Goods Sold (COGS)/Costs of Services (COS): all the costs directly involved in producing a product or delivering a service - notice the stress on directly. This includes the cost of the materials and labor directly used. What it does not include is the indirect costs, such as distribution costs, sales and marketing costs (that are normally shared across multiple units).

- Operating expenses: these are often called SG&A (Selling, General and Administrative Expenses), or overhead. They are the costs required to keep the company running from day to day: salaries, marketing, insurance, IT, etc. When analyzing the performance of a company, or when costs are too high, this is the first item to scrutinize. If a company is efficient it will keep this value low - or as minimum in line with the industry.

- Amortization and depreciation: this is a key concept that I partially covered in the balance sheet article, but it's worthwhile to add some extra context, this time from an income statement perspective. As recap, it is based on the same idea as accruals: we want to match as closely as possible the costs of our products and services with what was sold. This is achieved by spreading the cost of the expenditure over the useful (assumed) life of the item. When the asset is physical (e.g. a computer), we talk about depreciation, while when the asset is intangible (e.g. brand of an acquired company) the term amortization is used. An important point is that not all expenses go through this process: operating expenses (or opex) don't get neither depreciated nor amortized because they are considered short-term investments. Most companies follow the rule that any purchase over a certain dollar amount counts as a capital expenditure, while anything less is an operating expense. Also land doesn’t wear out, so accountants don’t record any depreciation each year. Remember when I mentioned accounting is an art?. Operating expenses show up on the income statement, thus reduce profit. Capital expenditures show up on the balance sheet, but the depreciation (of them) does end up on the income statement.

A couple important principles

Matching principle: the costs and expenses on the income statement are those the company incurred in generating the sales recorded during that time period. This seems intuitive, right? In fact, it is. The "artistic" part though is that companies often buy big batches of material they need for production, or they do capital investments (e.g. a truck, or machinery) that will be used for more than one fiscal period. In such cases the costs have to be allocated properly.

If for example a company has bought a forklift in February that plans to use over the following 5 years, the cost of such forklift should not show up on the income statement in February. Instead, the forklift is depreciated over the whole 5 years, with a portion (one-sixtieth) of the forklift's cost appearing as an expense on the income statement each month (assuming a simple linear depreciation). This is because of the matching principle.

Accrual principle: the cost is included only if it is referred to the fiscal year, it doesn’t matter if it has been paid or not to the supplier ---> the income generated during the year doesn’t necessary match with the cash flows (and that’s why we need the cash flow statement).

Putting it all together

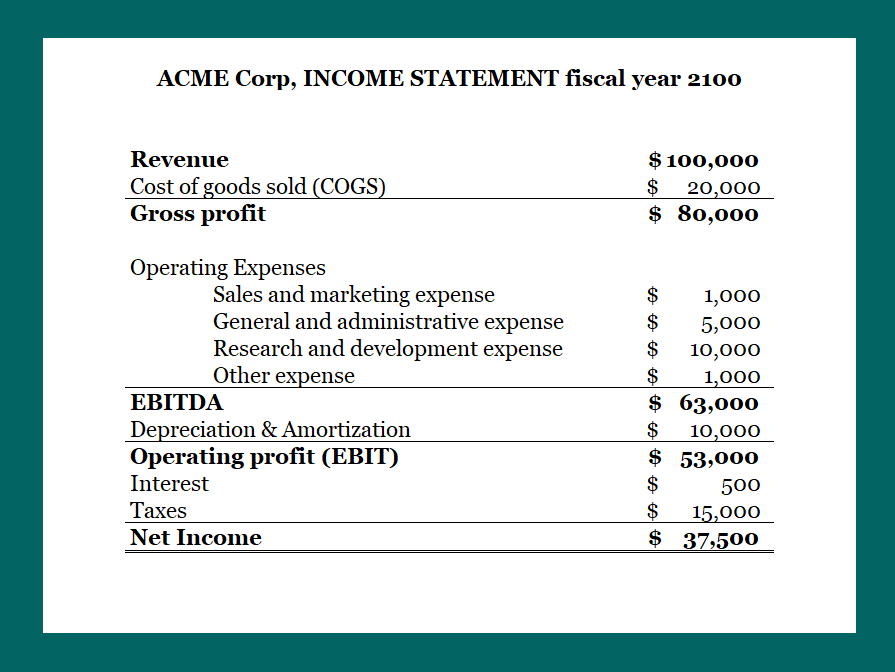

A very simple income statement would look like the below:

A couple notes:

- EBITDA: pronounced ee-bit-dah, it stands for Earnings before interests, taxes, depreciation & amortization. Very popular measure of corporate profitability as it's a proxy of cash profit generated by the company’s operations. It's typically one of the first things to look for when analyzing an income statement, especially when compared with the revenue or gross profit.

- Operating profit/EBIT: the two terms are often used interchangeably, although technically they don't always match. The key difference between EBIT (pronounced ee-bit) and operating profit is that operating profit does not include non-operating income, non-operating expenses, or other income. An example is gains or losses incurred by foreign exchange, or from investments not core to the company. EBIT stands for earnings before interest and taxes. The key difference between EBIT and EBITDA is that the former includes some non-cash expenses (the depreciated/amortized assets), whereas EBITDA includes only cash expenses. This makes a big difference for companies that are investments heavy as their depreciation will impact the EBIT but not the EBITDA.

Real life Examples

The example above is very simple, but what about the income statement of a couple real, and even better, famous companies? Let's take a look at THIS article.